by J.T. Murphy

by J.T. Murphy

“We will support the officials just so long as they rightly represent the workers, but we will act independently immediately they misrepresent them. Being composed of delegates from every shop and untrammelled by obsolete law or rule, we claim to represent the true feeling of the workers. We can act immediately according to the merits of the case and the desire of the rank and file”.*

One of the most noticeable features in recent trade union history is the conflict between the rank and file of the trade unions and their officials, and it is a feature which, if not remedied, will lead us all into muddle and ultimately disaster. We have not time to spend in abuse, our whole attention must be given to an attempt to understand why our organisations produce men who think in the terms they do, and why the rank and file in the workshops think differently.

A perusal of the history of the labour movement, both industrial and political, will reveal to the critical eye certain tendencies and certain features which, when acted upon by external conditions, will produce the type of persons familiar to us as trade union officials and labour leaders.

Everyone is aware that usually a man gets into office on the strength of revolutionary speeches, which strangely contrast with those of a later date after a period in office. This contrast is usually explained away by a dissertation on the difference between propaganda and administration. That there is a difference between these two functions we readily admit, but that the difference sufficiently explains the change we deny. The social atmosphere in which we move, the common events of everyday life, the people with whom we converse, the struggle to make ends meet, the conditions of labour, all these determine our outlook on life.

Do I feel that the man on the next machine is competing for my job? Do I feel that the vast army who have entered into industry will soon be scrambling with me at the works gates for a job in order to obtain the means of a livelihood? My attitude towards the dilution of labour will obviously be different to the man who is not likely to be subject to such an experience. That is why the Engineers have clashed with the Government officials. They are not likely to be subject to the schemes they have introduced, hence they can talk glibly about safeguards.

Now compare the outlook of the man in the workshop and the man as a full time official. As a man in the workshop he feels every change; the workshop atmosphere is his atmosphere; the conditions under which he labours are primary; his trade union constitution is secondary, and sometimes even more remote. But let the same man get into office. He is removed out of the workshop; he meets a fresh class of people, and breathes a different atmosphere. Those things which were once primary are now secondary. He becomes buried in the constitution, and of necessity looks from a new point of view on those things which he has ceased to feel acutely. Not that he has ceased to feel interested, not that he has become dishonest, not that he has not the interests of labour at heart, but because human nature is what it is, he feels the influence of new factors, and the result is a change of outlook.

Thus we obtain a contrast between those who reflect the working class conditions and those who are remote from them. Consider, now, the effect of this constitutional development. The constitutions invest elected officials with certain powers of decision which involve the members of the organisations in obedience to their rulings. It is true to say that certain questions have been referred to the ballot box ere decisions have been arrived at; but it is unquestionably true, also, that important matters have not been so referred, and increasingly insistent has been the progress towards government by officials. They have the power to rule whether a strike is constitutional or unconstitutional, and accordingly to pay or withhold strike pay. Local business must be referred for executive approval, and, where rules are silent, power to decide according to their judgment is theirs. The latter is probably the most important of all. It allows small groups who are, as we have already shown, remote from actual workshop experience to govern the mass and involve the mass into working under conditions which they have had no opportunity of considering prior to their inception. The need of the hour is a drastic revision of this constitutional procedure which demands that the function of the rank and file shall be simply that of obedience.

This is reflected in all our activities. We expect officials to lead, to shoulder responsibility, to think for us. Hence we get labour leaders, official and unofficial, the one in office, the other out of office, speaking and acting as if the workers were pliable goods, to be moulded and formed according to their desires and judgment. However sincere they may be, and we do not doubt the sincerity of the majority, these methods will not do.

Real democratic practice demands that every member of an organisation shall participate actively in the conduct of the business of the society. We need, therefore, to reverse the present situation, and instead of leaders and officials being in the forefront of our thoughts, the questions of the day which have to be answered should occupy that position. It matters little to us whether leaders be official or unofficial so long as they sway the mass, little thinking is done by the mass.

If one man can sway the crowd in one direction, another man can move them in the opposite direction. We desire the mass of men and women to think for themselves, and until they do this no real progress is made, democracy becomes a farce, and the future of the race becomes a story of race deterioration.

Thought is revolutionary: it breaks down barriers, transforms institutions, and leads onward to a larger life. To be afraid of thought is to be afraid of life, and to become an instrument of darkness and oppression.

The functions of an elected committee, therefore, should he such that instead of arriving at decisions FOR the rank and file they would provide the means whereby full information relative to any question of policy should receive the attention and consideration OF the rank and file, the results to be expressed by ballot. The more responsibility rests upon every member of an organisation the greater is the tendency for thought to be more general, and the more truly will elected officials be able to reflect the thoughts and feelings of the members of the various organisations.

Now we have shown some of the principal defects in the constitutional procedure, we will show how these defects have been and are encouraged by defects in the structure.

The ballot box is no new thing, every trade unionist understands the use of it, yet we find that when there is an election of officers, for example, or a ballot on some particular question, rarely more than forty percent vote; that means there are sixty percent who do not trouble. Being vexed with the sixty percent will not help us. An organisation which only stimulates forty percent to activity must be somewhat defective, and it is our duty to find those defects and remedy them.

A ballot is usually taken in the branches, and the meetings are always summoned meetings, so we will consider now the branch as a unit of the organisation. It is usually composed of members who live in certain areas, irrespective of where they work, and irrespective of the turn on which they work.

These are important factors, and account for a great deal of neglect. Men working together every day become familiar to each other and easily associate, because their interests are common. This makes common expression possible. They may live, however, in various districts, and belong to various branches. Fresh associations have therefore to be formed, which at the best are but temporary, because only revived once a fortnight at the most, and there is thus no direct relationship between the branch group and the workshop group. The particular grievances of any workshop are thus fresh to a majority of the members of a branch. The persons concerned are unfamiliar persons, the jobs unfamiliar jobs, and the workshop remote; hence the members do not feel a personal interest in the branch meetings as they would if that business was directly connected with their every day experience. The consequence is bad attendance at branch meetings and little interest. We are driven, then, to the conclusion that there must be direct connection between the workshop and the branch in order to obtain the maximum concentration on business. The workers in one workshop should therefore be members of one branch.

Immediately we contemplate this phase of our difficulties we are brought against a further condition of affairs which shows a dissipation of energy that can only be described as appalling. We organise for power and yet we find the workers in the workshops divided not only amongst a score of branches but a score of unions, and in a single district scores of unions, and in the whole of the country eleven hundred unions.

Modern methods of production are social in character. We mean by this statement that workers of all kinds associate together, and are necessary to each other to produce goods. The interests of one, therefore, are the interests of another. Mechanics cannot get along without labourers or without crane drivers; none of these can dispense with the blacksmith, the grinder, the forgemen, etc., yet in spite of this inter-dependence, which extends throughout all industry, the organisations of the workers are almost anti-social in character.

They keep the workers divided by organising them on the basis of their differences instead of their common interests. Born at a period when large scale machine production had not arrived, when skill was at a greater premium than it is today, many have maintained the prejudices which organisations naturally cultivate, while during the same period of growth the changes in methods of production were changing their position in relation to other workers, unperceived by them. With the advent of the general labour unions catering for men and women workers, the differences became organised differences, and the adjustment of labour organisations to the changes increasingly complex. The skilled men resent the encroachments of the unskilled, the unskilled often resent what appears to them the domineering tactics of the skilled, and both resent the encroachments of the women workers. An examination of their respective positions will reveal the futility of maintaining these sectional prejudices.

Consider the position of the skilled workers. They have years of tradition behind them, also five years apprenticeship to their particular trade. The serving of an apprenticeship is in itself sufficient to form a strong prejudice for their position in industry. But whilst the skilled unions have maintained the serving of an apprenticeship as a primary condition of membership, industrial methods have been changing until the all-round mechanic, for example, is the exception and not the rule. Specialisation has progressed by leaps and bounds. Automatic machine production has vastly increased. Apprenticeship in thousands of cases is a farce, for even they are kept on repetition work and have become a species of cheap labour. Increasingly are they set to mate men on piece work jobs, and although producing the same amount of work receive only 50 percent of the wages received by the men. It will be thus clearly perceived that every simplification in the methods of production, every improvement to automatic machine production, every application of machinery in place of hand production, means that the way becomes easier for others to enter the trades. So we can safely say that as historical development takes away the monopoly position of skilled workers it paves the way for the advancement of the unskilled.

Working in the same workshops as the skilled men, having to assist them in their work, seeing how the work is becoming simplified, knowing no reason satisfactory to himself why, having had to start life as a labourer, he should decline advancement and remain a labourer, takes time by the forelock, and ere long can compete with the rest on specialised work. So also enter the women workers, and thus ensues a struggle between craft, trade, and sex prejudices.

There are in industry seven millions of women workers, more than a million of whom have entered the engineering industry since the beginning of the war. How far they have been successful is no doubt a surprise to the majority of people. In addition to shell production, which has nearly passed into the hands of women, at least so far as the smaller kinds of them are concerned, we read in the Times Engineering Supplement of June 29th, 1917, an account of women’s work, from which the following is taken:

“In particular the Bristol exhibition was remarkable for the many hundreds of specimens of work wholly or mainly done by women. Apart from the still larger range covered by the photographs, fourteen separate groups of samples were shown, dealing respectively with aircraft engines, motor car engines, magnetos and other accessories of internal combustion engines, locomotive and stationary engines, guns and gun components, small arms, gauges, cutters and allied work, drawing dies and punches, welded and other aircraft fittings, aircraft framing and structural parts, projectiles, miscellaneous engineering, and optical and glass work. The list is long, but its very length summarises no more than fairly the variety of applications that are being made of women’s services in one work or another. A similar variety was seen in the composition of most of the individual groups. Details, for instance, were exhibited of several different aircraft engines, of motor car and motor lorry engines of a variety of makes, of “tank” (land ship) and Diesel engines; of the breech mechanism and other parts of a variety of guns, from the 3-pdr. Hotchkiss to the 8-in. howitzer, and, among small arms, of the Lewis and Vickers machine guns and the Lee-Enfield rifle. Over seventy punches and dies were shown for cartridge-drawing alone, and over a hundred varieties of shell-boring and milling cutters, twist-drills, and allied tools, and nearly as many separate parts of aeroplanes.”

That such production on the part of women is general it would be untrue to say, but it at least shows the tremendous possibilities before the women workers, how far the simplifying process has gone, and how the monopoly position of the skilled worker in all but heavy work has nearly gone. In many workshops, however, it can safely be said that women are not a success. As a matter of fact in some places there has been no attempt to make them a success. They are consequently tolerated with amused contempt as passengers for the war.

This position makes a grievous state of affairs for any post war schemes. It makes possible sham restoration schemes to which we all stand to lose by the magnitude of the unemployed market. Thousands of women may be turned into the streets, or become encumbrances on the men who may be at work or who also may be unemployed. Domestic service cannot absorb all women, as some suggest, nor is it possible, as others remark, for them to go back to what they were doing before the war. To put back the clock of history is impossible, and other solutions will have to be found.

It is true that woman labour is usually cheap labour; it is true that women generally are more servile than men (and they are bad enough); it is also true that they are most difficult to organise because of these defects, thinking less about such matters than men. For these reasons they are more the victims of the employing class. The blame is not altogether theirs. We men and women of today have now to pay the price of man’s economic dominance over women which has existed for centuries. Content to treat women as subjects instead of equals, men are now faced with problems not to their liking.

Yet everyone of the wage earning class, whether man or woman, is in the same fix. Each has to work for wages or starve. Each fears unemployment. The skilled men detest dilution because they fear the lowering of their standard of life by keener competition. The semi-skilled, and the unskilled, and the women each desire to improve their lot. All are in the hands of those who own the means of providing them with work and wages. Skilled men are justified in their desires, and so are the others. The only way the mutual interests of the wage earners can be secured, therefore, is by united effort on the part of all independent workers, whether men or women. Many have been the attempts in the past to bring about this result. Federal schemes have been tried, and amalgamation schemes advocated. Characteristic of them all, however, is the fact that always have they sought for a fusion of officialdom as a means to the fusion of the rank and file.

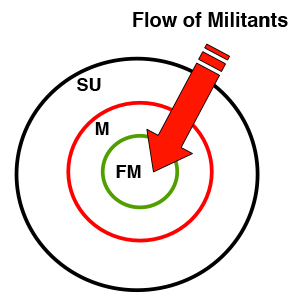

We propose to reverse this procedure. Already we have shown how we are driven back to the workshops. With the workshops, then, as the new units of organisation, we will now show how, starting with these, we can erect the structure of the Great Industrial Union, invigorate the labour movement with the real democratic spirit, and in the process lose none of the real values won in the historic struggle of the trade union movement.

The Workshop Committee

The procedure to adopt is to form in every workshop a workshop Committee, composed of shop stewards, elected by the workers in the workshops. Skilled, semi-skilled, and unskilled workers should have their shop stewards, and due regard be given also to the particular union to which each worker belongs.

For example:- Suppose a workshop is composed of members of the General Labourers’ Union, Workers’ Union, A.S.E., Steam Engine Makers, Women Workers, etc., each of these unions should have their shop stewards, and the whole co-operate together, and form the workshop committee.

Immediately this will stimulate the campaign for the elimination of the non-unionist. We know of one shop where, as soon as the workshop committee was formed, every union benefited in membership, and one society enrolled sixty members.

Where possible, it is advisable for shop stewards to be officially recognised and to be supplied with rules which lend support and encourage the close co-operation which a workshop committee requires.

We suggest the following as a shop steward’s instruction card, for any of the societies:-

- Members’ pence cards should be inspected every six weeks.

- New arrivals into workshops shall be approached by the shop steward nearest to such and questioned as to membership of a trade union.

- Steward shall demand the production of pence card of alleged member.

- Steward shall take note of shop conditions, wages, etc., in the area in which he is acting as shop steward, and report any violations of district conditions as approved by the trade unions which are not immediately remedied to the trade union officials.

- Any dispute arising between employer and employee, which results in a challenge of district conditions as approved, shall be reported to the shop steward.

- Steward shall then consult with other shop stewards as to the course of procedure to be adopted, the results of such consultation to be submitted to the members in the shop for approval.

- Matters which affect more than one department shall be dealt with in a similar manner by the stewards in the affected areas.

- The workers in the workshop should attempt to remedy their grievances in the workshop before calling in official aid.

- Where members of other unions are affected, their co-operation should be sought.

We would also advise that there be one shop steward to not more than fifteen workers. The more active workers there are the better and easier is the organising work carried on. Also, elect a convener in each shop for each class of worker. Their duties will be to call shop stewards’ meetings in the shop, and be delegates to the district meetings. Other duties we shall mention later.

The initiative should be taken by the workers in the various districts. It is immaterial whether the first move is made through the local trade union committees, or in the workshops and then through the committee, so long as the stewards are elected in the workshops and not in the branches. The means are then assured of an alliance between official and unofficial activities by an official recognition of rank and file control.

Having now described how the workshop committees can be formed, and how the committees can be at the same time part of the official trade union movement, we must now proceed to show how the movement can grow, and how it must grow to meet the demands of the day.

Local Industrial Committees

Local Industrial Committees should be formed in each district. It will be readily perceived that no one firm will be completely organised before the workers in other firms begin to move in the same direction. Therefore in the early stages of development, full shop stewards’ meetings should be held in every district, and an industrial administrative committee be formed from these meetings. The size of the committee will vary according to the size of the district, so we will leave that to the discretion of those who form the committee. The functions of these committees are mainly those of educating and co-ordinating the efforts of the rank and file through the shop stewards. For example, one committee provides information relative to agreed upon district conditions, Munitions Act, Military Service agreement, Labour Advisory Board, procedure in the workshops, etc. Then this committee should be the means of extending and developing the organisations, so that the workers can obtain the maximum of power in their hands.

The committee should not usurp the functions of the local trade union committees, but attend to the larger questions, embracing all the trade unions in the industry.

It will have been observed that we have addressed ourselves, so far as practical procedure is concerned, to the engineering workers. This we have done because the nucleus of the larger organisation has already come into being through that industry, and presents us with a clear line of development. So far, then, we have shown how to form a workshop committee, and an engineering workers’ committee in a locality. These committees should not have any governing power, but should exist to render service to the rank and file, by providing means for them to arrive at decisions and to unite their forces.

Works or Plant Committees

The next step is to intensify the development of the workshop committees by the formation in every plant of a plant committee. To achieve this, all the stewards of each firm, from every department of that firm, should meet and elect a committee from amongst them to centralise the efforts or link up the shop committees in the firm. The need for this development we will endeavour to make clear. Just as it is necessary to co-operate the workshops for production, so it is necessary to co-ordinate the work of the shop committees. As there are questions which affect a single department, so there are questions which affect the plant as a whole. The function of a plant committee, will be such that every question, every activity, can be known throughout the departments at the earliest possible moment, and the maximum of attention be rapidly developed. The complaints of workers that they do not know what is happening would become less frequent. The trick of ‘playing’ one department against another to cut rates could easily be stopped, and so on.

Without a central committee on each plant, the workshop committee tends to looseness in action, which is not an advantage to the workers’ movement. On the other hand with a plant committee at work, every change in workshop practice could be observed, every new department tackled as to the organisation of the workers in that department, and everywhere would proceed a growth of the knowledge among the workers of how intimately related we are to each other, how dependent we are each to the other for the production of society’s requirements. In other words, there would proceed a cultivation of the consciousness of the social character of the methods of production. Without that consciousness, all hope of a united working class is in vain, and complete solidarity impossible.

Instead of it being a theory of a few, that the workers are associated in production, the organisation of the workers at the centres of production will demonstrate it as a fact. Then will the smelters, the moulders, the labourers, forgemen, blacksmiths, etc., and all other workers, emphasise their social relationship, their inter-dependence in production, and the power they can be when linked together on a common basis. Consider this phase of development more closely, and how essential and valuable it is will become increasingly apparent.

Not only do we find in modern capitalism a tendency for nations to become self-contained, but also industrial enterprises within the nations tend in a similar direction. Enterprising employers with capital organised for the exploitation of certain resources, such as coal, iron and steel productions, etc., find themselves at the beginning of their enterprise dependent upon other groups of capitalists for certain facilities for the production of their particular speciality. The result is that each group, seeking more and more to minimise the cost of production, endeavours to obtain first hand control over all which is essential for that business, whatever it may be.

For example, consider the growth of a modern armament firm. It commences its career by specialising in armour plate, and finds itself dependent on outsiders for coal, transport, machinery, and general goods. It grows, employs navvies, bricklayers, joiners, carpenters, and erectors to build new departments. It employs mechanics to do their own repairs to machinery and transport. As new departments come into being a railway system and carting systems follow. Horses, carts, stables, locomotives, wagons, etc., become part of the stock of the firm. What men used to repair they now produce. With the enlargement of the firm electrical plant and motors, and gas producers are introduced, which again enlarge the scope of the management for production of goods for which hitherto they had been dependent upon outsiders. A hold is achieved on some coal mine, a grip is obtained of the railway system, and so at every step more and more workers of every description come under the control of a single employer or a group of employers.

We are brought together by the natural development of industry, and made increasingly indispensable to each other by the simplifying, sub-dividing processes used in production. We have become social groups, dependent upon a common employer or group of employers. The only way to meet the situation is to organise to fight as we are organised to produce. Hence the plant committee to bring together all workers on the plant, to concentrate labour power, to meet centralised capital’s power.

Local Workers’ Committee

We have seen how the formation of workshop committees has led us to the formation of an engineering workers’ committee and the plant committee in a locality. These in turn lead us to further local and national development. There are no clear demarcation lines between one industry and another, just as there are no clear demarcation lines between skilled, semi-skilled, and unskilled workers. A modern engineering plant, as we have shown, has in it workers of various kinds; besides mechanics, moulders, smiths, forgemen, etc., are joiners, carpenters, bricklayers, masons, transport workers, etc., all of which are dependent upon the engineering plant, and must accordingly be represented on the plant committee.

This drives us clear into other industries than engineering and makes imperative a similar development in these other industries as in the engineering industry. Then, just as from the trade union branches we have the trade council, so from the various industrial committees representatives should be elected to form the local workers’ committee.

It will be similar in form to a trades council, with this essential difference—the trades council is only indirectly related to the workshops, whereas the workers’ committee is directly related. The former has no power; the latter has the driving power of the directly connected workers in the workshops. So the workers’ committee will be the means of focussing the attention of the workers in a locality upon those questions which affect the workers as a whole in that locality.

The possibilities of such an organisation in a district are tremendous. Each committee will be limited by its nature to certain particular activities: the workshop committee to questions which affect the workshop, the plant committee to questions affecting the firm as a whole, the industrial committee to the questions of the industry, the workers’ committee to the questions relating to the workers as a class. Thus we are presented with a means of intensive and extensive development of greater power than as workers we have ever possessed before.

We have already shown in our remarks on the plant committee how industry progresses inside an engineering plant, and implies a similar development in other industries. One has only to consider modern machine development to readily realise that as machinery enters the domain of all industries, as transport becomes more easy and mechanical, all kinds of workers become inter-mingled and inter-dependent. Engineering spreads itself out into all classes of industry—into the mining industry, the building industry, into agriculture, etc., until we find, just as the other industrial workers have mingled with other engineering workers, so engineering workers and others intermingle with other industrial workers in their respective industries. The consequences are such that fewer situations arise, fewer questions come to the front affecting one industry alone or one section alone, and it becomes increasingly imperative that the workers should modify or adjust their organisations to meet the new industrial problems; for no dispute can now arise which does not directly affect more than the workers in one industry, even outside a single plant or firm.

A stoppage of much magnitude affects the miners by modifying the coal consumption, affects the railways by holding up goods for transport, and in some cases the railway workers are called upon, to convey “blackleg” goods and men to other centres than the dispute centres, and vice versa. A stoppage of miners soon stagnates other industries, and likewise a stoppage of railway workers affects miners, engineers, and so on. The necessity for mutual assistance thus becomes immediately apparent when a dispute arises, and an effective co-ordination of all wage workers is urged upon us. The workers’ committee is the means to that end, not only for fighting purposes, but also for the cultivation of that class consciousness, which, we repeat, is so necessary to working class progress. Furthermore, as a means for the dissemination of information in every direction, such a committee will prove invaluable, and reversing the procedure, it will be able to focus the opinions of the rank and file on questions relating to the working class as no other organisation has the facilities to do today.

To encourage and to establish such an organisation, however, demands cash to meet the expenses involved. In order therefore that even in this matter the class basis shall be recognised, we recommend that associate membership cards be issued from the workers’ committee. The card should contain a brief statement of the objects we have in view, and space for the entrance of contribution, which should be nominal in amount. The manner of collecting contributions can be easily carried out, as follows: let the contribution be paid to the shop steward, who will enter the amount on the card provided, the stewards will then pay over to the convenor of the shop, who will in turn, pay over the amount to the treasurer of the workers’ committee at the shop stewards’ meeting, each checking the payments of the other.

National Industrial Committees

The further extensive development in the formation, of a national industrial committee now demands our attention, for it will be readily agreed that the local organisations must be co-ordinated for effective action.

We are of the opinion that the local structure must have its counterpart in the national structure, so we must proceed to show how a national industrial committee can be formed. In the initial stages of the movement it will be apparent that a ballot for the election of the first national committee would be impossible, and as we, as workers, are not investing these committees with executive power there is little to worry about. Therefore a national conference of delegates from the local industrial committees should be convened in the most convenient centre. From this conference should be elected a national administrative committee for that industry, consideration being given to the localities from which the members of the committee are elected. Having thus provided for emergencies by such initial co-ordination the first task of the committee is to proceed to the perfecting of the organisation.

It will be essential for efficiency to group a number of centres together for the purpose of representation on the national administrative committee of the industry. We would suggest twelve geographical divisions, with two delegates from each division, the boundaries of the division depending upon the geographical distribution of the industry. The functions of the committee should be confined to the focussing of questions of a national character relating to the industry. It must be clearly understood that the national industrial committee is not to usurp the functions of the executive councils of the trade unions. Power to decide action is vested in the workshop so far as these committees are concerned.

If the occasion arises when the rank and file are so out of touch with the executive councils of their unions that they take action in spite of them, undoubtedly they would use whatever organisation lay to hand. Apart from such abnormal circumstances the functions of the committee should be confined to the building up of the organisation, to the dissemination of information throughout the workshops of all matters relating to the industry, initiating ways and means of altering the structure and constitutions of the trade unions, and working with the true spirit of democracy until the old organisations are so transformed that the outworn and the obsolete are thrown off, and we merge into the larger, more powerful structure we have outlined.

National Workers’ Committee

But just as we found it necessary to arrive at the class basis in the local workers’ committee, so it is essential that we should have the counterpart to it to the national workers’ committee. Again we find that history justifies the development. As the trade unionists of the past felt that there was a community of interest between all trade unionists in a locality, and formed the trades council, so they eventually found a similar move on national lines necessary and formed the trades union congress. Its counterpart in our movement is the national workers’ committee. To form this we suggest two delegates should be elected from each national industrial committee. The smallness of the committee will not be a disadvantage. Of its nature it will confine itself to questions which affect the workers as a whole. The financial relationship of the industrial committees and the national workers’ committee can be arranged at the conferences when the initial steps are made to the formation of the committees.

Having outlined the manner in which the structure can grow out of the existing conditions, we would emphasise the fact that we are not antagonistic to the trade union movement. We are not out to smash but to grow, to utilise every available means whereby we can achieve a more efficient organisation of the workers, that we all may become conscious by an increasing activity on our part how necessary each worker is to the other for production and for emancipation.

Unity in the workshop must come first; hence we have dealt more in detail with the shop committees than the larger organisations growing out of them. Not for a moment would we lay down a hard and fast policy. The old mingles with the new. Crises will arise which will produce organisations coloured by the nature of the questions at issue. But apart from abnormal situations we have endeavoured to show a clear line of development from the old to the new.

Working in the existing organisations, investing the rank and file with responsibility at every stage and in every crisis; seeking to alter the constitution of every organisation from within to meet the demands of the age; working always from the bottom upwards—we can see the rank and file of the workshops through the workshop committees dealing with the questions of the workshops, the rank and file of the firms tackling the questions of the plant as a whole through the plant committee, the industrial questions through the industrial committees, the working class questions through the working class organisation—the workers’ committee. The more such activity grows the more will the old organisations be modified, until, whether by easy stages or by a general move at a given time, we can fuse our forces into the structure which will have already grown.

So to work with a will from within your organisations, shouldering responsibility, liberating ideas, discarding prejudices, extending your organisations in every direction until we merge into the great industrial union of the working class. Every circumstance of the age demands such a culmination. The march of science, the concentration of the forces of capitalism, the power of the State, the transformation of the military armies into vast military industrial armies, all are factors in the struggles of the future, stupendous and appalling to contemplate. During the greatest war in history—an engineers’ war—the British Government can allow 80,000 to 90,000 engineers to cease work for three weeks. Let the war cease, liberate the vast number of industrial workers from the army, and what becomes of our petty strike? It sinks into insignificance.

“His Majesty’s Government will place the whole civil and military forces of the Crown at the disposal of the railway companies…” So said the Premier of 1911 to the railway men. So will say the Premier of England tomorrow. The one mighty hope, the only hope, lies in the direction indicated, in a virile, thinking, courageous working class organised as a class to fight and win.

* Hinton, ‘The Clyde Workers Committee and the dilution struggle’ in Briggs & Saville, Essays in Labour History, Vol. II, 1971

Text from the LibCom site with corrections made in reference to the hard copy

edition published by Class War Classix

www.libcom.org – Class War Classix

by Emile Pouget

by Emile Pouget